For the Love of Money

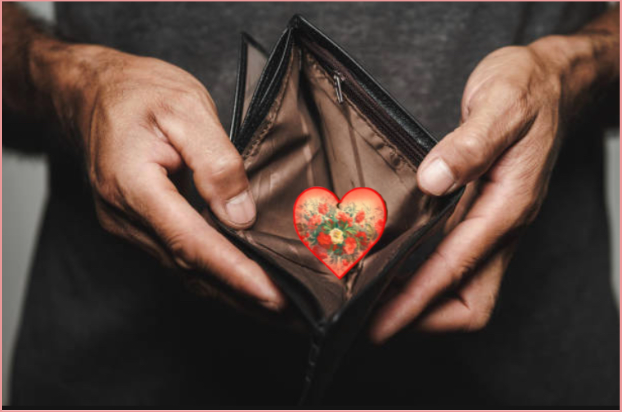

Nothing says America like a commercialized celebration of love. February 14th is wrought with expectations to exchange gifts, flowers and food. To teenagers luxuriating off minimum wage, that shopping list looks daunting. Does young love warrant spending come Valentine’s season?

Valentine’s Day spending averages about $23.9 billion each year, with 53% of all consumers celebrating through economic activity, and men spending about two times as much money as women. Rightfully so, believes one female student: “a girl should not pay.” Her predicted Valentine’s Day plans include a dinner with her honeybun, all expenses paid.

Curiously, she harbors some hate for the “stupid holiday,” which pressured participants to “show [their] love in one day because everyone else thinks [they] have to.”

This narrative doesn’t define all couples. In one partnership, a sweetheart explained that she’s spent over 600 dollars on her beloved. “He doesn’t buy me sh*t! I spend the money in this relationship!” In the past, she’s demanded that he opt out of buying her birthday gifts. Her boyfriend explained that he was aware that they are subverting gendered expectations, but that they were not doing so for any progressive reason. It seems that accidentally resisting patriarchal norms may be a byproduct of his “brokenness.” They, too, plan on treating the 14th as a regular day and avoiding flamboyance.

In the middle of both poles exists a self-described “low-key couple” planning for mutual gift-giving between both genders. They both happened to enjoy the holiday and look forward to spending their first Valentine’s Day together.

Two students debated the value of Valentine’s Day. One student mentioned that they saw Valentine’s Day as a cash grab, and another countered that some people expressed their love through acts of service. The latter did not see any reason for affection to be demonized, especially if those emotions were unbiased and could be extended to family as well. The students disagreed about who the day is meant for, with the first student insisting that sweethearts are the intended participants, and the day is meaningless if one is not romantically involved.

Haters of the love day also take issue with its prioritization of couples. An anonymous retail worker compared his experiences as a singleton to celebrating as someone’s boo boo bear, saying, “When I was single I hated Valentine’s Day. I would see people post on their stories and…just wanted to like [physcially express frustration towards] them.”

After he got a significant other, his perspective totally changed. Now, he even thinks Valentine’s Day is “cool,” and uses it to remember people without a special someone. So he also spreads love to his pals, a homage to his old life when friends were all he had. He mentioned that gift-giving was one way he appreciated his loved ones, though he limited the presents to his love bug.

I approached a student in my gym class on the receiving end of fondness from her partner. To her, the affection felt special in a way she wouldn’t appreciate if they were just friends. This girl expressed the ineffable feeling of Valentine’s Day; she appreciated the feeling of being “shown off” online, and posted on social media, where her relationship could be announced digitally. “If I’m posted, I’m happy,” she declared simply. “Meow.”

On request, she shared some of the material he’s published about the two of them. In one photo that appeared on his private Snapchat story, the pair’s faces fill up the screen horizontally, as they look wide-eyed at the camera. His hand cups the side of her face as his lips form a subtle pout. Against a dark background, they would be the main focus of the photograph if not for a sticker reading 6:09 PM; the centerpiece of this work of art.

The second photo she shared seems candid, as our interviewee inspects herself in the mirror, finger raised toward her head, mid-hair adjustment. Another sticker adorns this image, reading “Good Morning” in bold gold font. This was also posted to her boy’s story, which she estimates has an audience of 40 people.

If social media exists as an outlet to project an idealized version of oneself publicly, then advertisements regarding relationship status are only natural. Behold a secondary form of marketing, except this time symbolism isn’t quite as obvious as obnoxious red and pink hearts. As the modern explorer scrolls through a vast virtual landscape, their insecurities are carefully considered. This online world is intelligent, ruled by the algorithm which responds to the forlorn and pushes forth posts and videos of youths just like the user happily showcasing their fulfilling relationship. This loner is bound to feel that they’re being left out of some rite of passage as they spend Valentine’s Day with their phone.

In an exercise of consideration, one couple stated that they will be opting out of making any affectionate posts on the upcoming holiday.

Yet some students feel they can separate life from the social media version. Two single girls found there to be nothing obnoxious about two others halves to take to celebrating on the ‘net. Maybe it is just another “love language.”

For all the displays of affection between couples that this holiday brings, singles shouldn’t feel alienated. Even without a swain, love is not in vain. Singles can either take February 14th as a day to remember that “no one loves me and I hate it,” or “an opportunity to show love to the people around you”— people you appreciate with or without romance. And if these people are friends, you can rest assured that probably you won’t be broken up with on Valentine’s Day, as one poor student was. Probably.

Despite all this discussion of Valentine’s stentorian messaging, there was little understanding of how it started among polled students. Actually, one interviewee theorized that “because queens were given a lot more stuff than kings,” women traditionally get more Valentine’s gifts.

Historians generally hold a slightly different understanding of Valentine’s Day’s evolution. In the 5th century, the combination of two pagan ragers, Lupercalia (which involved the sacrifice of male goats and a dog) and St. Valentine’s Day created a day for fertility and love. Meanwhile, Vikings from northern France, called Normans, held Galatin’s day, which centered around the beginning of the bird’s mating season. Galatin translates to “lover of women,” but the “G” in the word is sometimes pronounced as a “V,” which is suspected to be the etymological origin of the modern holiday.

The day gained popularity across Britain and Europe through Shakespeare and Chaucer’s romanticized perspective. Shakespeare created characters that “[had] witchcraft in [their] lips” in Henry V – Act 5, Scene 2, and Chaucer declared that nothing “is better than a woman.”

After handmade cards took off in the Middle Ages, Valentine’s Day really started to be commercialized in the 19th century amidst the industrial revolution. While interchangeable parts and factory-made clothes became all the rage, producers began selling manufactured valentines. The shelves have expanded ever since to display Bouqs, Hershey and Hallmark come February.

Valentine’s Day has come a long way, and it wouldn’t still be celebrated if there wasn’t something that attracts consumers. As one person put it, they choose to participate “because [of] tradition, but it’s also nice to have a day for…[love].” Indeed.

Iris is a Junior writer for the Bulldog Reporter. Outside of Newspaper club, Iris is interested in writing, filming, editing and producing short films,...