Community Solar- Bringing Clean Energy Further

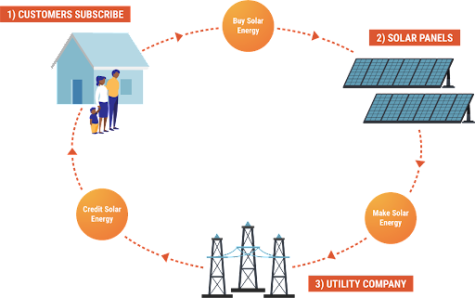

Since 2019, solar energy has become increasingly accessible. Community Solar, for instance, created by the New Jersey Board of Utilities, gives residents access to solar energy from afar through the grid.

In 2006, the program was piloted when a large town collectively funded the installation of solar panels. Electricity generated through solar fusion was successfully sent from the utility grid to each home. In turn, a portion of the 18,000 town members’ energy came from the solar panels.

Community solar has expanded through the advent of Multifamily Affordable Solar Housing (MASH), bringing community solar to lower-income apartment complexes and buildings. MASH participants received reduced energy bills, split between the tenants. Community solar thus saves residents, on average, between 5 and 15 percent of their electricity bill, though there’s variation based on location, proximity to projects, and energy consumption. The season also impacts savings, as summer and spring seasons correlate with greater solar energy production.

While community solar is notably cheaper than PSE&G, Frontier Utilities, or any other traditional alternative, on-site solar panels are the most economical option.

The Biden Administration expanded the Federal Tax Credit for Solar Photovoltaics (aka ITC), meaning people who install a PV system from 2022 to 2023 will get a 30% tax credit based on the price of their installation. This deduction will decrease by 4% in 2024 and an additional 4% in 2034.

On average, households with their own solar systems save $9,000 on electricity over the course of their PV system’s lifetime. This can be paired with more savings as the surplus of energy generated can be sold to houses involved in community solar grids.

Plus, for every 1,000 kWh of energy created by a solar system, owners get one Solar Renewable Energy Credit (SREC), a voucher that can be exchanged for real money. The exchange rate fluctuates, but one currently sells for ~$212 according to NJSREC.

Bigger solar producers can also contribute to community solar- and get rewarded for it. Clean Renewable Energy Bonds (CREBs) offer electrical co-ops, electrical municipal utilities, and public utility districts an interest-free loan for clean energy projects.

They also have access to several related tax credits (reductions on taxes), from the EPA’s 2005 insurance of up to $80 Million in CREBs tax credit bonds to the Energy Improvement and Extension Act’s 2008 insurance of 1.6 Billion of CREBs. Utility-sponsored projects can get cash benefits with their projects, although the tax impact on individual participants is minimal.

These benefits are a part of states’ incentives to meet solar quotas or renewable portfolio standards. But sitting down with a solar panel salesman, it seemed clean energy initiatives faced another obstacle: energy conglomerates.

The solar representative recounted a previous customer who moved into a new home. She’d had solar panels installed at her previous house and was excited to get panels set back up at her new place. She has a number of neighbors with solar panels installed, and her home was determined to be an ideal location with adequate sunlight. The company assumed they would be able to install a PV system again and went ahead with the process without the approval of her township.

Shortly after the system’s installation, she got a notice from the town that the panels would have to be removed. PSE&G announced that due to the frequency of solar energy systems in the neighborhood, they ran the risk of overwhelming the grid and close-circuiting the area.

The solar salesman wondered if the PSE&G’s worries about the grid’s maximum capacity conflicted with privatized interests. It’s no coincidence, he asserted, that a move away from traditional energy dependence would create profit losses.

The company’s power in advising the township was another cause for concern to him. How can the nation meet Biden’s 2050 net-zero carbon emission goal if conglomerates can restrict customers’ clean energy options?

Beyond savings, centralized solar power makes sustainability easier for homeowners, including people not eligible for solar panels due to shade or HOA restrictions. Switching to solar energy in any capacity cuts water consumption, reduces carbon, nitrogen oxide, and greenhouse gas emissions, and produces no fossil fuel.

Biden’s 2023 water cut proposition makes water consciousness relevant: with water shortages in the Colorado River, households in Arizona in drought without access to Scottsdale’s water supply, and a 25-year-long drought ravaging the Midwest, lifestyle adjustments will likely soon be necessary to cope with America’s limited water supply.

As a low-carbon source of energy, community solar is one of the few alternatives (aside from nuclear energy) to the dominant fossil fuel-dependent forms of electricity that drive climate change. In fact, listed among the United Nation’s top ten climate actions is making the switch to wind and solar power for residential energy.

Community solar is also an attractive option amidst concerns regarding foreign fuel dependency. Residential energy in the United States comes from a mix of coal, natural gas, and petroleum, which the United States isn’t entirely able to produce independently. As of 2021, the Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported that the United States imports 8.47 million barrels of petroleum per day from 73 countries. The EIA also noted that, historically, petroleum is the highest source of energy consumption. Sunlight is obviously international and sidesteps all potential foreign energy trade insecurities.

Ultimately, community solar offers benefits ranging from renewability to the possibility of the country’s energy self-sufficiency, and for this, it, as well as energy conglomerates’ efforts to oppose it, demand heightened recognition..

Iris is a Junior writer for the Bulldog Reporter. Outside of Newspaper club, Iris is interested in writing, filming, editing and producing short films,...