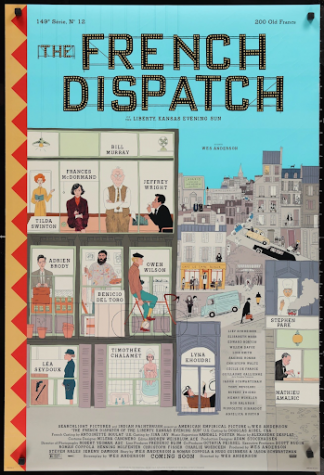

A Tribute to Journalism: The French Dispatch

Wes Anderson’s film “The French Dispatch” was unique. I say that because it was not filmed with the initial goal of pleasing the audience with a rich storyline or flowing smoothly. Rather, it was created as a memoir to writers all around the world. More specifically: journalists. Spoilers ahead, obviously.

The film was inspired by Wes Anderson’s love for “The New Yorker” magazine. In it, Arthur Howitzer Jr. , the French Dispatch’s editor-in-chief, suddenly dies from a heart attack. His will stated that the newspaper would be shut down immediately following one final issue. This issue recaps three past stories, plus an obituary written for Howitzer.

First, there is “The Concrete Masterpiece”, a work about a prodigy artist sentenced to 50 years in prison for double homicide, who becomes a national treasure due to his special talents. “Revisions to a Manifesto”, a love story hidden under a student protest movement that receives world attention, and an important game of chess, acts as the second story, and the last goes “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner”, a television interview recapping the abduction of the Commissioner’s son, told in the 3rd and 1st perspective of the same character.

All three stories end in a heartwarming epilogue, in which the writers join together and create the obituary for what is to be “The French Dispatch’s” final issue.

When watching the film, the one and only criticism I could think of would be that the flow of the film was, at the very least, confusing. Though I understood the flow and storyline, many other movie reviewers, including my immediate family, were left scratching their heads over what they just saw. They see that as lazy writing and over-directing.

I see it as something completely different, however.

The film was not meant to tell a three-act story, after which audiences would exit the theater and be able to go on with their day without pondering what they had just seen. The confusing structure was exactly how Anderson intended it to be. To the audience, it’s a complex movie. To writers, it’s a love letter. The rich tones in each story, with the addition of Anderson’s craft in the film, makes it a textbook example to digest when searching for deeper meanings.

A perfect example of how Anderson’s craft was so well-thought out was in all three stories themselves. In the film, when the stories are being told, they are mostly represented in black and white. This hints at the idea that we are “reading” a newspaper, hearing the narration from the third person point of view.

Yet when the characters start to speak for themselves, they are portrayed in a colored world. It is as if our imaginations of “reading” the article are so vivid that we can visualize what these characters are saying.

The beautiful world of “The French Dispatch” is at heart a message to writers and journalists all over the globe, telling them to “create.” The motif of creation in the film is vivid in all three pieces as well.

“The Concrete Masterpiece” is all about the creation of artwork by a complex mind. “Revisions to a Manifesto” is about creating a work of literature to spread a message. The final piece shows how cooking is an art form of its own and how its creation can yield beautiful works of food.

I could go on and on with the countless aspects of craft that Anderson used when creating this concrete masterpiece. And that’s the beauty of the work. You can rewatch it over and over and still find something you didn’t spot before. Exactly how Anderson intended.