Mr. Anderson, Ol’ Reliable

“It’s campy, it’s pretentious, it’s artsy, it’s not even that coherent,” praises Colin Szustakowski.

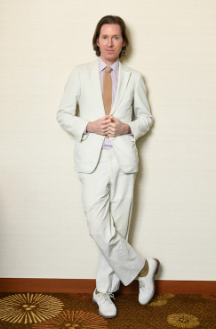

Wesley Wales Anderson. Behind that coy smile and corduroy suit is the mind that has manufactured almost a dozen instantly recognizable films. His style is unmatchable, and his control as a director is evident in his attention to coloring, costumes, background, dialog, and symmetry. Throughout his career, he won best original screenplay winner for his work with Grand Budapest Hotel and became a Seven-time Academy Award nominee. Beyond his official accolades, he is beloved by many.

He got his beginning with Bottle Rocket (1992), despite its title, his first creation wasn’t explosive. It plays like a film made by friends. That’s just what it is: Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson, University of Texas students, created short films for their local cable access station while Anderson majored in philosophy. Bottle Rocket the short film became Bottle Rocket the movie (1996) after its success at Sundance Film Festive.

The film version follows wannabe crime members Dingan and Anthony Adams in their odd friendship. Dingan, meticulous and over-exaggerated, commands Anthony and Bob Mappelbeth, a temporary getaway driver, to follow him on a petty crime spree meant to get the attention of Dingan’s former landscaping company. As their irascible leader, Dingan engineers Anthony’s “escape” from a self-check-in mental facility, a break-in to Anthony’s home, and a stick-up at a bookstore.

This film holds the beginnings to many of Wes Anderson’s trademarks. Notably, Bottle Rocket’s closing scene ends with a slo-mo of Dingan looking over his shoulder at Anthony and Bob while a penny whistle cries underneath. As the marimbas play, Dingan exits defeated but not disheartened, finally demoted from his self-appointed leadership role.

In his directing career since Bottle Rocket, Anderson recreates dynamics like these: groups of strange characters led by a mixed-up white man (Royal Tenenbaum, Arthur Howitzer Jr., Max Fischer, Jack Witman, Steven Zissou, and arguably Mr. Fox); people who come off as goofy for taking themselves too seriously (Dingan, Chas Tenenbaum, Max Fischer); composed and eloquently spoken children (Anthony’s sister, Max Fishcher, Suzy Bishop, Sam). Anderson would also return to the slo-mo in almost all of his following films, each time accompanied by some whimsical score underneath. In hindsight, these details are recognizable as precursors to his identifiable style. But he exercised caution as an emerging director, creating a genre film that didn’t particularly stand out.

I liked Wes Anderson’s storytelling style to the Magic Treehouse series. Mary Pope Osborn has created a niche and a historical fantasy formula for Jack and Annie. In all 37 books, the siblings travel back to a different time in the treehouse, meet some odd educational figures and end up back where they started. After Bottle Rocket (1996) and Rushmore (1998), Anderson also became very comfortable in his self-made lane. Call it consistency or repetition, a source of comfort or neophobia, but his flicks ensure personality-driven conflicts.

Of course, these personalities are a bit twisted. Experiencing his films feels like watching a cast full of manic pixie dream girls, which is to say that every character has a whimsical demeanor and a weirdness about their role. A middle brother, embarrassed to have a pregnant wife out of fear of divorce. An overprotective single father raising ripped sons ready for any emergency. A shadowy cider-guarding rat turned kidnapper. An athlete who’s fallen from fame to fall into love with his step-sister.

“I kind of feel like he’s parodying American storytelling and the way we do it in movies, . . . where he takes kind of these conventional plots but then orients them in individual characters. . . . A lot of, historically, [America’s] biggest movies are rooted in not as much narratives but as in the actions, the things that are happening, the story that’s being told rather than the characters themselves. . . . His movies are very well written in that sense,” says junior Colin Szustakowski, film club co-founder.

The ingredients of a recognizable Wes character go beyond just identity. For one thing, the way the characters talk to each other is carefully cultivated. Notably, Anderson creates characters with a controlled range of emotions. The former doesn’t mean each character is totally bottled up; nay, emotional vulnerability moves the plot and resolves tensions. The brothers in The Darjeeling Limited (2007) are pulled along on a vacation, organized obsessively by Francis, the eldest. As the group enters the second act, they’ve already acknowledged the growing distrust between them and now huddle together under the mutual feeling of rejection from their mother, and an “I’m sorry” is even released.

But there’s a specific line between the amount of vulnerability Wes’s characters are permitted to express. They may cry, may even admit that they are crying, but we’ll never see big blubbering tears or puffy red faces. Desire is also portrayed with a human layer missing. The underage marriage between Francis and Suzy happened abnormally fast. We learn that they’ve grown closer as pen pals, but the majority of those letters are never revealed, leaving their intimacy to spring itself upon us. In The French Dispatch (2021) Moses, incarcerated artist, and Simone, his taciturn guard, strike up a partnership first as muse and painter and later develop a silent compassionate bond. I find these trends almost mesmerizing, devoid of sappiness or romanticization. Sometimes, lines like “Also, I suppose I feel sad” come off as robotic. The response, “please turn away, I feel shy about my new muscles,” is equally so. But deadpan delivery and excessive formalization are tendencies of Anderson’s characters.

“Dear Suzy. I am sorry that your brothers are so selfish. Maybe they will grow out of it”. writes lover Sam.

“Can you back away a little? You just spit in my eye,” requests brother Francis.

“That cab has a dent in it,” observes Dudley Heinsberg, medical abnormality.

The audience certainly isn’t slapping their knees at any of these lines, and granted, neither are the characters hearing them. In fact, the single moment across Anderson’s filmography, when one character laughs at another, wasn’t mutual or hysterical. When Sam laughs at the idea of Suzy Bishop’s parents reading a book about parenting difficult children in Moonrise Kingdom (2012), she gets offended rather than joining in on what could have been self-aware banter. The audience looks on, stone-faced.

In general, joking is scarce (especially in The French Dispatch), but dialog can still hold a subtle type of situational humor. There are moments that warrant a gust of air out the nose. Like Royal Tenenbaum’s attempt at consoling his grandsons for their loss and telling them that “Your mother was a very attractive woman.” When I re-watched The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) with the film club, the moment was recognized and appreciated without a snicker.

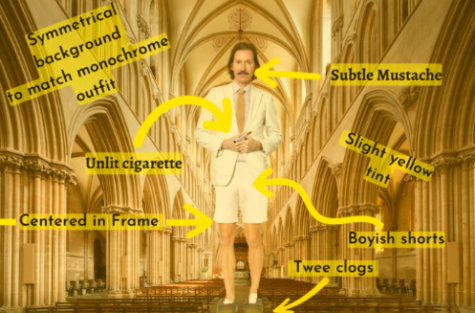

The creator of many similar fantasy worlds, Wes Anderson has a fondness for the whimsical. Blake Sydne, screenwriter and author, said that every character needs a limp and an eye patch, and Anderson took that advice to heart, particularly in dress. Andersonian garb has a dainty feel, expressed in funny hats, thick glasses, pets as accessories, facial hair, and vaguely vintage layered jackets. Each personal costume tries to convey that conformity is anti-Anderson. In Wes World, everyone calls on the rotary phone, uses morse code, and drives peculiar automobiles. Printed shirts and jeans aren’t sold here. Smoking is super cool (Margo Tenenbaum has been since age twelve). People’s actions may be unpredictable, but fashion is totally orderly. This control appeals to Anderson’s fans, captivated by his pleasant, recognizable style.

My pet theory is that the people most attracted by his aesthetic vision resonate with the hyper individuality he instills in his characters and wish, deep down, to be categorized as all Wes creatures are (Though ironically, an over-saturation of quirkiness makes them no longer unique). The mega fans just want to project the same twee air that works so well in Wes’s composed universe.

Outside of the film world, it’s quite hard to transform oneself into an Anderson character divorced from the music, setting, and camera angles that have cemented his niche. Through the human eye, the world is a static shot. Through Wes’ camera, we can be guided deliberately. Shots push in, move horizontally, or vertically, rarely combine directions. They center characters, draw eyes explicitly to details and move between walls. Wes Anderson describes the backdrop of The Life Aquatic and The Darjeeling Limited as“sets” in the real world that are incapable of “actually moving with the story.” Here lies my concern for people infatuated with Anderson’s universe: Real-life mediocrity can’t compete with Anderson’s reality. One must be careful not to envy a fictitious life.

I briefly eluded to Anderson’s tendency to put a troubled white man at the helm of his tales but I didn’t mention the people Wes puts under them. Without fail, nearly every character of color in these movies serves the main family, acts as an entertainer or plays the exotic love interest. In The Grand Budapest Hotel, the only Mexican character, Tony Revolori, plays the discombobulated lobby boy. Yes, he has white co-workers who are also at bellhops, but as the Jr. Lobby Boy in training, he’s situated below them in the workplace hierarchy. Although the story is narrated from his perspective,

he only follows his promiscuous hotel manager as they flee murder allegations. He never advances past protégé status or gains much agency in their relationship. In The Royal Tenenbaums, there are two people of color interacting with the main family. Pagoda plays the extension to the extension, plus one to a man re-entering the lives of his adult children and almost ex-wife. Pagoda effectively follows Royal from their doctor’s shtick to short-lived bellhop work to a hospital and then to a wedding in the final scene. Never do we see any hint of Pagoda’s life beyond Royal. He objects to Royals actions with a quick stab to the gut but also stays with him to help him heal and get back on his feet.

Both Pagoda and Zero contrast the white majority and are portrayed not as independent beings, but as lesser assistants to the rest of the cast. This expectation of assistance is also present in Wes’s portrayal of multi-racial relationships. Danny Glover is the second non-white character in The Royal Tenenbaums, and he courts Etheline a few degrees removed from the rest of the family. Royal attempted to exploit his outsider status by first insulting Glover and then suggesting that he wouldn’t be able to do anything about it. As Glover begins to defend himself, Royal further demeans him, asking if he “wants to talk some jive.” Yelling ensues, and Royal continues to agitate, finally admitting that he wants Glover out of his house. In his tantrum, Royal touches upon an important racial phenomenon in Wes’ characterization: the unspoken unity within the coalition of the white characters. His audience can feel the distance; we never get to see the full extent of Glover’s character while he has to work to be liked in an exclusionary environment. We never even know that he has a son until the very last scene.

Love interests in Bottle Rocket and Darjeeling Limited, Amara Karan and Inez, are similarly constricted. Both non-white actresses play almost the same role: a short-lived female fling that the rest of the group disapproved of. While we got to hear the gossip from the white trios, the women only got to briefly support the white stars. Support is putting it nicely. They moved dauntingly fast into intimacy, seemingly propelled by some unseen force of attraction between characters, took up the interest of one of the co-stars for some time before breaking things off. They became an obstacle for the main character to part ways with, leaving behind an undeveloped and almost pointless woman on their adventure. If a race-based Bechdel test is invented, the Royal Tenenbaums and the Grand Budapest Hotel would both fail. Bottle Rocket and Darjeeling Limited fail the real-life Bechdel test.

Similarly, Isle of Dogs plays with Anderson’s interest in language barriers as it is set in Japan, a backdrop critics take issue with. The film never provides subtitles for the Japanese characters, making the language barrier tangible and blocking a section of the audience from proper engagement with Japanese dialog. Even the dogs’ barks were rendered in English. Another point of contention is the English-speaking foreign exchange student and activist, Tracy Walker. She is the character who initially fights for the alienated dogs and investigates the murder of Major Domo. She recognizes government propaganda misleading the Megasaki inhabitants and exposes Watanabe’s evil anti-dog intentions. The sequence feels unrealistic, the only white person happens to expose corruption and rescue the dogs. The basis of Anderson’s films are himself, and a portrayal of his view of the world may have to be white-centric. But if you are going to put people of color in your movie, perhaps there should be some consideration of their development, and they should be presented as three-dimensional active characters. Silencing them (to non-Japanese- speaking audience members) almost puts them below the fluent dogs in terms of agency.

An anonymous student wondered if “this trend of putting non-white individuals as side characters is seen throughout Hollywood. It seems kind of more like a mainstream movie maker’s thing”. Perhaps the aforementioned critiques are applicable to a range of films. Even so, Anderson’s racial archetypes and flawed representation can’t go unnoticed while discussing all that he’s created.

There’s an air of transformation on the Western front. The French Dispatch , Anderson’s most recent piece, diverges slightly from the typical formula. Although he employs a number of his favorite old camera moves, (slow pans, booms, pushes in, wide shots), he also resists many of his trademarks. There are almost no overhead shots, or zooms and a higher frequency of close-ups. He also flips the typical pastel tint on it’s head by coloring a portion of the film in black and white. This unlocked a new method of direction over the picture by drawing the audience’s attention to specific shots in color. Saoirse Ronan’s blue eyes for example, are emphasized before cutting back to black.

Secondly, following the title card, “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner” there’s potential for a break from his typical racial character construction. Roebuck Wright, a black food critic, is tasked with writing an article about a great chef. Write attends dinner with the Commissar of the Ennui police force, but ends up witness to the kidnapping of the Commissar’s son, Gigi. The son uses morse code to signal for the police force to “send the cook”, Chief Lt. Nescaffier. Nescaffier, the cook, prepares a poisoned dish for the criminals and is forced to test it himself, thus ingesting the poison, but he ends up surviving and experiencing a totally new flavor. As Nescaffier

recovers, he bonds with Write over being considered outsiders in France. Write may disagree on the significance of the exchange, but the moment is raw and intimate and feels like Anderson’s genuine attempt to give his characters of color emotional independence. Initially, it feel like this could mark the beginning of Anderson’s move away from racial disregard. But Write is actually based on the real-life black writer James Baldwin. Baldwin wrote elegantly about his anger at the constant inhumanity faced, and it ultimately motivated him to flee from American racism to France, the setting of The French Dispatch (2021). In an essay on Richard Wright, published in 1951, Baldwin wrote: “And there is, I should think, no Negro living in America who has not felt briefly and for long periods, with anguish sharp or dull, in varying degrees or to varying effect, simple, naked and unanswerable hatred; who has not wanted to smash any white face he may encounter in a day, to violate, out of motives of the cruellest vengeance, their women, to break the bodies of all white people and bring them low, as low as that dust into which he himself has been and is being trampled.” How would he feel anesthetized by a white American director, who cut his distinctive social prose down to a couple of lines?

recovers, he bonds with Write over being considered outsiders in France. Write may disagree on the significance of the exchange, but the moment is raw and intimate and feels like Anderson’s genuine attempt to give his characters of color emotional independence. Initially, it feel like this could mark the beginning of Anderson’s move away from racial disregard. But Write is actually based on the real-life black writer James Baldwin. Baldwin wrote elegantly about his anger at the constant inhumanity faced, and it ultimately motivated him to flee from American racism to France, the setting of The French Dispatch (2021). In an essay on Richard Wright, published in 1951, Baldwin wrote: “And there is, I should think, no Negro living in America who has not felt briefly and for long periods, with anguish sharp or dull, in varying degrees or to varying effect, simple, naked and unanswerable hatred; who has not wanted to smash any white face he may encounter in a day, to violate, out of motives of the cruellest vengeance, their women, to break the bodies of all white people and bring them low, as low as that dust into which he himself has been and is being trampled.” How would he feel anesthetized by a white American director, who cut his distinctive social prose down to a couple of lines?

Roebuck Wright: This city is full of [foreigners], isn’t it? I’m one myself.

Lt. Nescaffier: Seeking something missing, missing something left behind.

Roebuck Wright: Maybe with good luck, we’ll find what eluded us in the places we once called home.

Sweet. From a regular couple of fictional characters, these lines could practically be material for video essays. We’re talking about interesting themes here, and finally really acknowledging identity, both between characters and with the agency Anderson allots to both of them. But think, the muse lived through the assassination of MLK, felt crushed by the failures of this country and its painstaking ideas about progress. He talked to the Wilmingington 10, wrongfully convicted on arson charges because they had the audacity to desegregate their schools. He lived through heights of the KKK, forced bussing, segregationist Govenor George Wallace, racist encounters with the police, and wrote with anger at a time when Regan and the rest of America shunned him. It’s somehow hard to imagine that this same man would support the co-opting of his image. Historical figures must be remembered, but there’s careful consideration necessary to avoid misrepresenting the people they were. Anderson may work in his own between fictitious historical genre, but he must be sensitive to his contributions to comforting myths and perhaps unintentionally softening the blow of such a powerful writer and critic.

I admire Anderson for trying to create depth in his characters, but it seems he still has room to grow. His upcoming film, Asteroid City, is set in Saudi Arabia and provides him with an opportunity to continue experimenting or revert to his familiar quaint and limiting style.

Iris is a Junior writer for the Bulldog Reporter. Outside of Newspaper club, Iris is interested in writing, filming, editing and producing short films,...